I just had an experience much like the experiences of those Adirondack locals who were left out of the equation while the discussions about the rules and regulations of the ADK Park at its beginnings were taking place. I live in a very rural place. There are horse farms and corn fields and essentially nothing else until the nearest town, which takes about 7 minutes to get to and STILL has about 5 antique stores for every restaurant. (I think there are 3 restaurants). I have no cell service in my house, and you have to walk about a mile and a half to the top of the road to be able to get anything remotely close to the amount of signal you'd need to make a phone call. I've lived in this place for 19 years (my entire life), as many of the Adirondack locals probably did as well. And, therefore, I've gone my whole life without ever having more than one bar of cell service in my house. This can be an inconvenience, but more than anything, it has created a community between my family, the families around us, and the entirety of the private boarding school campus on which I live. This includes my good friend Meg (who's in Janelle's section of this class with me!), who attended Millbrook for 4 years, and also had to deal with the inconvenience that comes from the lack of cell phone service.

This past week, Meg posted a blog post about the necessity of the installation of a cell phone tower near Millbrook's campus. She referred to the opinion of the students, herself included, regarding the isolation that comes from not being able to use your cell phone to call your friends back home, or you family. She then referred to the side opposed to the cell tower: the weekenders coming up from NYC, and looking for a relaxing, rural escape. I read the post and thought, "Wait, I don't fit into either of those groups." Yes, I was once a Millbrook student, but I am also a local resident of the area, and definitely not a weekender with a primary home in New York City. Both of these groups are outsiders (on a very extended vacation, for the boarding students), and although I'm sure this was just an oversight on Meg's part, it was still a disheartening feeling to be left out. I felt protective of my landscape and wanted to have my opinion against the cell tower heard and respected. I find this analogous to the conflict between inside and outside control of the Adirondack Park that we have talked about so much, and this feeling of not being included in my own area's decisions has made me understand why internal control, to some extent, is so important. For the residents of the park to abide by the rules and regulations religiously, they must also agree that said terms are appropriate and useful. They should be able to have their opinions about the land they reside in heard. This conflict, however, is not resolved because of the unbelievable amount of outsider control that led to the ultimate creation of the park. This instance (and it is a BIG instance) shows why outsider control, and a possibly less emotional connection with the land, can lead to more practical decisions. Without the outsider control preserving the land for business and industry purposes, the Adirondack Park would probably not exist, at least not to the extent that it does today. Essentially, we need a way for outsider control to contribute their unemotional opinion while still allowing the often less powerful insiders to be heard and respected.

PSA: Meg knows I fully respect her opinion and she approved this blog post being written!

Saturday, November 1, 2014

The Adirondack Powder Skiers Association and Possible Amendments to the SLMP

On the Adirondack Almanack today, I saw an article that interested me greatly. The Adirondack Powder Skiers association is pushing for an amendment to the Adirondack State Land Master Plan (SLMP) to allow for the maintenance of ski trails and glades on forever wild land. This could potentially be the first time the SLMP is amended in over 25 years.

First, some background information is necessary to understand the issue. Backcountry skiing has been a huge part of Adirondack culture since the 1930s, when the CCC program resulted in the cutting of many ski trails in the high peaks. Before ski lifts and developed areas became widespread, these trails were very popular. With the advent of ski lifts however, these trails were barely used and often neglected. The hiking trail up Wright Peak was actually relocated onto the bottom half of the ski trail, creating potential for dangerous collisions between hikers and skiers.

In the 1970s, backcountry skiing became popular once more due to the advent of the Ski to Die Club. These intrepid skiers made bold and harrowing descents all over the high peaks; Ron Konowitz, the club's founder, became the first and only skier to ski all 46 high peaks. Lately, backcountry skiing has seen an even larger resurgence due to increasingly lightweight equipment, and a public desire to escape the relative comfort and safety of developed ski areas. Every year the Mountaineer hosts the Adirondack backcountry ski festival, bringing professionals like Glenn Plake to the high peaks, and offering classes to educate the public. The Adirondack Powder Skiers association is looking to build on the recent momentum of backcountry skiing in the Adirondacks.

Anyone who hikes in the high peaks immediately notices all the brilliant, white and gray bedrock scars littering the steep mountainsides. These natural slides provide great natural ski trails; the caveat is that they not only require a high level of ski expertise, but also knowledge of how to safely travel in avalanche terrain, and strong wilderness skills. To those unprepared, a journey onto one of the slides could have perilous consequences. Aside from these slides, there are very few trails or "glades" designated for skiing in the high peaks. Konowitz, the founder of the Adirondack Powder Skier Association, is pushing for the right to maintain ski trails and glades on forever wild land by removing blowdown and trimming underbrush. He believes that this will give skiers a safer option in the Adirondack backcountry and keep them off hiking trails, which will prevent collisions between skiers and hikers on the narrow, winding paths.

On one hand, while Konowitz is pushing for minimal maintenance of ski trails, this could be another "foot-in-the-door" scenario. If the amendment to the SLMP is passed, will we eventually see huge, ugly swaths of clear-cut forests all for the sake of skiing? This occurred (illegally) a couple years ago on Big Jay Mountain in Vermont. Also, could this potential amendment of the SLMP set the stage for other, more drastic changes? On the other hand, Konowitz is a very experienced Adirondack traveller and wilderness advocate. Considering his skiing resumé, it is unlikely that he would ever approve of anything more than minimal maintenance. In addition to this, backcountry skiing is one of the least-impactful recreational activities on the Adirondack land because it is only practiced when the ground is protected by layers of snow. In my opinion, it is kind of ridiculous that minimal maintenance ski trails are prohibited, while hiking trails and even horse trails form a vast web all over the Adirondacks. Just like the rail-trail issues, public forums are being set up to discuss the potential changes.

If anyone is interested in reading about these issues, here are two good articles. (disclaimer: both the articles and my opinion are written from pro-skier stances.)

http://www.powder.com/stories/adirondack-amendment/

http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/10/commentary-backcountry-skiers-seek-slmp-amendments.html

First, some background information is necessary to understand the issue. Backcountry skiing has been a huge part of Adirondack culture since the 1930s, when the CCC program resulted in the cutting of many ski trails in the high peaks. Before ski lifts and developed areas became widespread, these trails were very popular. With the advent of ski lifts however, these trails were barely used and often neglected. The hiking trail up Wright Peak was actually relocated onto the bottom half of the ski trail, creating potential for dangerous collisions between hikers and skiers.

In the 1970s, backcountry skiing became popular once more due to the advent of the Ski to Die Club. These intrepid skiers made bold and harrowing descents all over the high peaks; Ron Konowitz, the club's founder, became the first and only skier to ski all 46 high peaks. Lately, backcountry skiing has seen an even larger resurgence due to increasingly lightweight equipment, and a public desire to escape the relative comfort and safety of developed ski areas. Every year the Mountaineer hosts the Adirondack backcountry ski festival, bringing professionals like Glenn Plake to the high peaks, and offering classes to educate the public. The Adirondack Powder Skiers association is looking to build on the recent momentum of backcountry skiing in the Adirondacks.

Anyone who hikes in the high peaks immediately notices all the brilliant, white and gray bedrock scars littering the steep mountainsides. These natural slides provide great natural ski trails; the caveat is that they not only require a high level of ski expertise, but also knowledge of how to safely travel in avalanche terrain, and strong wilderness skills. To those unprepared, a journey onto one of the slides could have perilous consequences. Aside from these slides, there are very few trails or "glades" designated for skiing in the high peaks. Konowitz, the founder of the Adirondack Powder Skier Association, is pushing for the right to maintain ski trails and glades on forever wild land by removing blowdown and trimming underbrush. He believes that this will give skiers a safer option in the Adirondack backcountry and keep them off hiking trails, which will prevent collisions between skiers and hikers on the narrow, winding paths.

On one hand, while Konowitz is pushing for minimal maintenance of ski trails, this could be another "foot-in-the-door" scenario. If the amendment to the SLMP is passed, will we eventually see huge, ugly swaths of clear-cut forests all for the sake of skiing? This occurred (illegally) a couple years ago on Big Jay Mountain in Vermont. Also, could this potential amendment of the SLMP set the stage for other, more drastic changes? On the other hand, Konowitz is a very experienced Adirondack traveller and wilderness advocate. Considering his skiing resumé, it is unlikely that he would ever approve of anything more than minimal maintenance. In addition to this, backcountry skiing is one of the least-impactful recreational activities on the Adirondack land because it is only practiced when the ground is protected by layers of snow. In my opinion, it is kind of ridiculous that minimal maintenance ski trails are prohibited, while hiking trails and even horse trails form a vast web all over the Adirondacks. Just like the rail-trail issues, public forums are being set up to discuss the potential changes.

If anyone is interested in reading about these issues, here are two good articles. (disclaimer: both the articles and my opinion are written from pro-skier stances.)

http://www.powder.com/stories/adirondack-amendment/

http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/10/commentary-backcountry-skiers-seek-slmp-amendments.html

Friday, October 31, 2014

Beavers are Gaining New Respect

I plan to do my final project on beavers and, thanks to Onno, I was directed to a NY times article on beavers that was published October 27, 2014. It's very interesting to think about the change in human opinion of beavers throughout history. In some of our earlier readings it was clear that the beaver was looked at as a pest that needed to be removed by humans. Also, beaver hats were so popular in England in the 15th century that beavers were extirpated from New York and almost the entire East cost by 1640. The beaver remained almost completely extirpated from the East cost till their reintroduction in the early 1900s to the Adirondacks and similar areas. What early settlers failed to realize is the essential role that beavers play in local ecosystems. Beavers are essential to raising the water table along creeks and streams, which allows trees and plants to grow on the banks which secures the soil and protects it from erosion. It is also very difficult to replicate a beaver dam. The Western US is starting to realize their need for beavers' complex dams, as the hydroelectric dams become a point of contention for environmentalists and power companies. Beaver dams provide an eco-friendly solution to the dam problem in the West, although it seems like common sense, it's taken engineers years to admit that the beaver is still the best dam solution. Not only are Beavers instinctually inclined to stop running water, their dams also require no burning of fossil fuels or poring of cement. It's very likely that beavers are the most sustainable solution to almost any problem that originates from low water tables.

The Forest Preserve Wasn't Enacted to Actually Preserve the Forest? What?

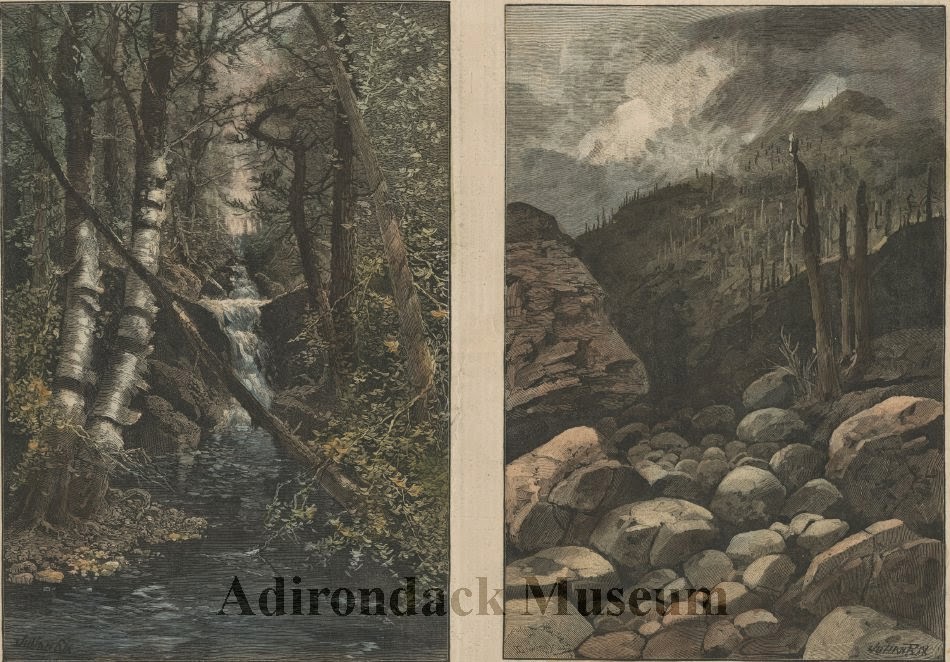

At the beginning of Scheinder's "Forever Wild" chapter, Schneider mentions two engravings depicting the Adirondacks that were published in the January 24, 1885 issue of Harper's magazine. There are two prints; One entitled, "A Feeder of the Hudson, as it was," and the other, "A Feeder of the Hudson, as it is." I did a little digging and found the prints that Schneider was referring to.

On the left is the first image, "A Feeder of the Hudson, as it was" and on the right is "A feeder of the Hudson, as it is." In these prints, by Julian Rix, we see two completely different landscapes. The first one shows a beautiful and lush landscape with moss covered rocks, a flowing waterfall, and towering trees. In the second image, we see a barren landscape with tree stumps, and even a smoldering one that appears to have been burned just moments before. These prints really capture the drastic change that occurred in the 19th century in the Adirondacks as logging became more and more prevalent.

I was very surprised when Schneider asserted that no one was concerned with preserving the "wilderness for its own sake," (220) but more so for more utilitarian and commercial purposes. Verplanck Colvin highlighted this commercial concern in his legislative report that "The Adirondack Wilderness contains the springs in which are the sources of our principal rivers, and the feeders of our canals. Each summer the water supply [...] has lessened, and commerce has suffered," (222). Even once the Forest Preserve was enacted, Schneider points out that there was no legislative protection for the trees of the Adirondacks. But Schneider isn't surprised as he reiterates that the "neither the Forest Preserve nor the Adirondack Park was created out of a desire to preserve wilderness in any prehumanized sense, " (224).

I had always assumed that the Adirondack Park and the Forest Preserve were made first and foremost out of a concern for the actual inhabitants and ecology of the area. Then again, the Adirondacks have a long history of economically driven movements. While it is difficult to understand this mindset from a contemporary framework, these legislations were beneficial to the Adirondacks, no matter what the original intent was in the 19th century.

On the left is the first image, "A Feeder of the Hudson, as it was" and on the right is "A feeder of the Hudson, as it is." In these prints, by Julian Rix, we see two completely different landscapes. The first one shows a beautiful and lush landscape with moss covered rocks, a flowing waterfall, and towering trees. In the second image, we see a barren landscape with tree stumps, and even a smoldering one that appears to have been burned just moments before. These prints really capture the drastic change that occurred in the 19th century in the Adirondacks as logging became more and more prevalent.

I was very surprised when Schneider asserted that no one was concerned with preserving the "wilderness for its own sake," (220) but more so for more utilitarian and commercial purposes. Verplanck Colvin highlighted this commercial concern in his legislative report that "The Adirondack Wilderness contains the springs in which are the sources of our principal rivers, and the feeders of our canals. Each summer the water supply [...] has lessened, and commerce has suffered," (222). Even once the Forest Preserve was enacted, Schneider points out that there was no legislative protection for the trees of the Adirondacks. But Schneider isn't surprised as he reiterates that the "neither the Forest Preserve nor the Adirondack Park was created out of a desire to preserve wilderness in any prehumanized sense, " (224).

I had always assumed that the Adirondack Park and the Forest Preserve were made first and foremost out of a concern for the actual inhabitants and ecology of the area. Then again, the Adirondacks have a long history of economically driven movements. While it is difficult to understand this mindset from a contemporary framework, these legislations were beneficial to the Adirondacks, no matter what the original intent was in the 19th century.

Thursday, October 30, 2014

Cell Towers; a necessary eyesore

After discussing cell towers and reading the article that Janelle had sent to us

(http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/10/feds-preserve-local-jurisdiction-over-cell-towers.html?utm_source=Adirondack+Explorer+%26+Adirondack+Almanack&utm_campaign=4fd31f5869-Adirondack_Almanack_RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_b49eb0d11b-4fd31f5869-47298733)

I think I need to play devils advocate for a moment. Going to school at a pretty remote prep school I find a lot of parallels with the Adirondacks. Millbrook New York, acted as the weekend escape for many city dwellers who could afford to have a second home to ride horses and drink tea. This became a home to anyone looking for a rural retreat from "real life". Sound familiar? We also had the issue of putting in cell towers. While the family retreating for the weekend from these overused technologies could have cared less about having no signal on their phone all weekend (partly because it was just the weekend), as a student trapped with no contact outside of my school bubble I felt much differently. Having no signal on campus was inconvenient to say the least and at times a safety hazard. I can see why in both Millbrook and the Adirondacks people would fight to avoid the building of these "eyesores", but for people who live in these places and don't have the means to escape these "escapes" we need to be able to use modern technology especially our cell phones, not just in the one spot on campus where you can find semi decent service. So I know this may go against our anti modernization theme but speaking as someone who has struggled with this issue, I would have welcomed this eye sore with open arms.

(http://www.adirondackalmanack.com/2014/10/feds-preserve-local-jurisdiction-over-cell-towers.html?utm_source=Adirondack+Explorer+%26+Adirondack+Almanack&utm_campaign=4fd31f5869-Adirondack_Almanack_RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_b49eb0d11b-4fd31f5869-47298733)

I think I need to play devils advocate for a moment. Going to school at a pretty remote prep school I find a lot of parallels with the Adirondacks. Millbrook New York, acted as the weekend escape for many city dwellers who could afford to have a second home to ride horses and drink tea. This became a home to anyone looking for a rural retreat from "real life". Sound familiar? We also had the issue of putting in cell towers. While the family retreating for the weekend from these overused technologies could have cared less about having no signal on their phone all weekend (partly because it was just the weekend), as a student trapped with no contact outside of my school bubble I felt much differently. Having no signal on campus was inconvenient to say the least and at times a safety hazard. I can see why in both Millbrook and the Adirondacks people would fight to avoid the building of these "eyesores", but for people who live in these places and don't have the means to escape these "escapes" we need to be able to use modern technology especially our cell phones, not just in the one spot on campus where you can find semi decent service. So I know this may go against our anti modernization theme but speaking as someone who has struggled with this issue, I would have welcomed this eye sore with open arms.

Wednesday, October 29, 2014

Early Adirondack Photography

Our discussion about early

Adirondack paintings and folk music sparked my curiosity about other forms early

Adirondack art, such as photography. I found out that Seneca Ray Stoddard

(1844-1917) was one of the first artists to capture the majesty of the Adirondack

landscape through photography. Before his career as a photographer, Stoddard

had successfully captured Adirondack scenes through his paintings, and later

through his photographs, he was able to continue capture not only the reality of the

Adirondack environment, but also document the ever-changing landscape. Stoddard's

photographs illustrated the timeless natural beauty of the Adirondacks' along

with the changes that resulted from logging and mining, and the development of

hotels and railroads. That is, as mining and logging devastated much of the

Adirondack landscape, Stoddard successfully documented the loss of the wilderness

and used his images to foster a new ethic of responsibility for the landscape. He captured the sublime beauty of the Adirondack landscapes, often combining it with a human presence. His unique vision did much to create the market for these Adirondack views,

doing much to instill an awareness of the Adirondacks that encouraged greater

appreciation of nature.

http://www.nysm.nysed.gov/virtual/exhibits/SRS/Vision/index.html#

Monday, October 27, 2014

Autumn: The Chemistry Behind the Colors

Every year during approximately three weeks of autumn, tens of thousands of people flock to the Adirondacks to see the beautiful colors of the changing trees. While people enjoy green forests, the reds, oranges, and yellows satisfy another level of love for the outdoors. I will talk about the chemistry behind how the leaves change color and try not to confuse you:

Chlorophyll is the primary molecule involved in energy-producing processes in plants and is responsible for plants' colors. It absorbs light of a certain wavelength - which matches up to a shade of red - to excite electrons to a higher energy state which cascade through other molecules to create energy. The interesting thing about this molecule is that it is not very stable (i.e. it doesn't like to exist in its environment in a leaf), so it decomposes shortly after being synthesized by a plant. Thus, plants must continually synthesize it to continue living and this requires nutrients. Plants also have what are called accessory absorbers that absorb different wavelengths of light and transfer this energy to chlorophyll to create more energy for the plant's processes. Some of these are also responsible for the beautiful fall colors we see every year; they are carotenoids, flavinoids, and anthocyanins. These are also unstable and continually decompose, but are not nearly as unstable as cholrophyll.

When the tree senses that winter is coming, it starts a process called abscission which essentially blocks off nutrients to leaves by blocking their transport from the leaf's stem. When this happens, the plant can no longer synthesize chlorophyll. However, the leaf does not immediately fall off because the accessory absorbers do not decompose as quickly as chlorophyll does because they are more stable than chlorophyll. This is where the color comes in. Since is chlorophyll no longer present to absorb red light - and reflecting green light - that red light is now being reflected. Carotenoids, flavinoids, and anthocyanins each absorb different wavelengths of light within the green spectrum and thus reflect red, orange, and yellow. Different species use these molecules to different extents and that is why different species appear different colors during the fall after chlorophyll has decomposed.

See these articles for more detail:

http://equipped.outdoors.org/2014/10/why-do-leaves-turn-different-colors.html

http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/fallcolr/fallcolr.html

Picture from: http://www.adirondack.net/fall/leaf-peeping-guide.cfm

Chlorophyll is the primary molecule involved in energy-producing processes in plants and is responsible for plants' colors. It absorbs light of a certain wavelength - which matches up to a shade of red - to excite electrons to a higher energy state which cascade through other molecules to create energy. The interesting thing about this molecule is that it is not very stable (i.e. it doesn't like to exist in its environment in a leaf), so it decomposes shortly after being synthesized by a plant. Thus, plants must continually synthesize it to continue living and this requires nutrients. Plants also have what are called accessory absorbers that absorb different wavelengths of light and transfer this energy to chlorophyll to create more energy for the plant's processes. Some of these are also responsible for the beautiful fall colors we see every year; they are carotenoids, flavinoids, and anthocyanins. These are also unstable and continually decompose, but are not nearly as unstable as cholrophyll.

See these articles for more detail:

http://equipped.outdoors.org/2014/10/why-do-leaves-turn-different-colors.html

http://scifun.chem.wisc.edu/chemweek/fallcolr/fallcolr.html

Picture from: http://www.adirondack.net/fall/leaf-peeping-guide.cfm

American Progress?

The painting from class today that most piqued my interest was American Progress, which was painted by Asher Brown Durand, an artist of the Hudson River School, in 1853. I found the painting interesting because of its surreal and grand depiction of an idealized rather than realistic landscape, which we learned was characteristic of art of the Hudson River School.

To the left side of the painting, we see an uncivilized and unsettled wilderness--the forests seem overgrown and untouched relative to the tidy vegetation of the settled landscape to the right. In the distance, there seem to be smoke stacks, which suggests an urban landscape--the highest degree of civilization. As we follow the road forward and to the left, the landscape seems to become gradually less civilized--we see what appears to be a small town with a church steeple followed by a log cabin and finally the unsettled wilderness (if you don’t consider the native americans). We talked in class today about the role of time in art, which I think is especially relevant here. Although the painting depicts a specific moment, it also portrays changes in the landscape that could only occur over generations. Based on the direction of the wagons on the road, we conclude that the progression of the painting is from right to left (or, equivalently, east to west). This painting made me think back to Wandering Home, in which McKibben contrasts the relatively unsettled wilderness of New York with the more civilized, pastoral landscape of Vermont. The white church steeple in the distance seems especially reminiscent of Vermont.

It seems as if this painting does not perfectly parallel the settlement of the Adirondacks. In the painting, civilization seems to be a dominant and inexorable force--we are led to believe that the entire landscape will eventually resemble the city in the distance, even though the natives clearly present a challenge to this "progress". However, this was not the case with settlement in the Adirondacks. Early human attempts to conquer the wilderness were mostly unsuccessful. Moreover, the effort to preserve Adirondack wilderness suggests that the force of human settlement is not a strong as the painting suggests and a backward progression in time.

By the way, I could have written a similar post for the painting Manifest Destiny, which was painted about 20 years after American Progress by another American Artist, John Gast. Check it out--the composition and allegorical meaning of the two works are very similar.

Georgia O'Keeffe

From 1918 to 1934, Georgia O'Keeffe lived for part of the year on Lake George in the Adirondacks. Georgia O'Keeffe, like Kent Rockwell, is a more recent Adirondack painter. There are definitely some similarities between O'Keeffe and Rockwell, especially with their use of color and shape. She differs from the more realistic landscape painters before her (like Durand or Tait) in that she pushed the boundaries between the descriptive and the abstract. Abstract shapes are important to her work. Her style generally emphasizes the feeling of the scene she paints, and not necessarily how it actually looked.

O'Keeffe's paintings are concentrated versions of classic Adirondack paintings. They are not realistic, but the traditional orange-red coloring is vividly present in Lake George Autumn, and this painting portrays a classic Adirondack topic: a lake and mountains. O'Keeffe seems to only focus on what is most important to her, and that seems to be shape and color. Her paintings exude a lot of emotion and movement, and reflect the wild nature of the Adirondacks.

|

| Georgia O'Keeffe, Lake George Barns, 1926, oil on canvas (http://www.afanews.com/articles/item/1860-modern-nature-georgia-okeeffe-and-lake-george) |

|

| Georgia O'Keeffe, My Shanty, Lake George, 1922 (http://www.wikiart.org/en/georgia-o-keeffe/my-shanty-lake-george) |

|

| Georgia O'Keeffe, Lake George Autumn, 1927, oil on canvas (http://collection.mam.org/details.php?id=5948) |

O'Keeffe's paintings are concentrated versions of classic Adirondack paintings. They are not realistic, but the traditional orange-red coloring is vividly present in Lake George Autumn, and this painting portrays a classic Adirondack topic: a lake and mountains. O'Keeffe seems to only focus on what is most important to her, and that seems to be shape and color. Her paintings exude a lot of emotion and movement, and reflect the wild nature of the Adirondacks.

Lake George shoreline restoration

The attached news story popped up in my daily Adirondack Almanack email, and I thought I would pass it on.

To summarize: About 150 feet of shoreline was eroding into Lake George, largely due to the clay soils. This resulted in turbidity, which is a term for hazy water caused by suspended particles. The Lake George Association and the Friend's Point Homeowners' Association joined forces to prevent further shoreline erosion. People often repair shorelines using structural approaches such as concrete walls, but such approaches are expensive and environmentally harmful. Therefore, the LGA and the Friend's Point Homeowner's Association decided instead to use vegetation to stabilize the shoreline. The article refers to this technique as bioengineering. Since waves crash along the shoreline, they lined the new shoreline with a stormwater fabric called "Grow Sox" before planting native vegetation.

I am not sure how widely this method is used, but I am impressed by how involved and yet noninvasive it is.

http://blog.hulettsonlakegeorge.com/index.php/archives/3142?utm_source=Adirondack+Explorer+%26+Adirondack+Almanack&utm_campaign=bbbc688ba1-Adirondack_Almanack_RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_b49eb0d11b-bbbc688ba1-47316029

To summarize: About 150 feet of shoreline was eroding into Lake George, largely due to the clay soils. This resulted in turbidity, which is a term for hazy water caused by suspended particles. The Lake George Association and the Friend's Point Homeowners' Association joined forces to prevent further shoreline erosion. People often repair shorelines using structural approaches such as concrete walls, but such approaches are expensive and environmentally harmful. Therefore, the LGA and the Friend's Point Homeowner's Association decided instead to use vegetation to stabilize the shoreline. The article refers to this technique as bioengineering. Since waves crash along the shoreline, they lined the new shoreline with a stormwater fabric called "Grow Sox" before planting native vegetation.

I am not sure how widely this method is used, but I am impressed by how involved and yet noninvasive it is.

http://blog.hulettsonlakegeorge.com/index.php/archives/3142?utm_source=Adirondack+Explorer+%26+Adirondack+Almanack&utm_campaign=bbbc688ba1-Adirondack_Almanack_RSS_EMAIL_CAMPAIGN&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_b49eb0d11b-bbbc688ba1-47316029

Dudes in the Adirondacks

We have been talking a lot about people who go to the woods to experience life in a different way for a little while. These people weren't much different from the movement that happened at approximately that same time as ranchers out West began to supplement their income from ranching by also bringing in tourists so they could experience a little of what life was like on the prairie. The similarities are striking: you had a variety of options for the sort of experience that you wanted, from more rustic on a real working ranch to more carefree on a vacation oriented ranch, and just as the guides in the Adirondacks were romanticized and often characterized by a specific persona the cowboys of the vacation ranches were even asked to play the "cowboy" role. The most interesting difference to me is that the tourists out West were called "dudes" and the ranches they visited were called "dude ranches." "Dude" was a term applied to all tourists, regardless of age or sex. A side-note to this is that around the same time as white-tailed deer were being extensively hunted in the East, bison were being hunted equally vigorously out West. They have experienced a come-back similar to that of the beavers.

But while looking up these ranches, I happened upon an article talking about dude ranches in the Adirondacks. Apparently, after the era of the great camps, and starting around 1930, a large number of ranches sprang up in Warren County (Lake George/Sacandaga area) to the point where Warren County was known as the dude ranch capital of the East. They basically provided a Western flavored vacation experience including horseback riding and some rodeo action. People would come from the cities to meet the cowboys and to be in that sort of vacation atmosphere. The ranches even imported some cowboys from the West, and remained popular until the 70's and 80's when the focus of the tourists changed yet again. Some continue to exist today with slightly changed business models.

While this may seem corny to most (it would to me too if I had never heard of a dude ranch), I would argue that it's just another way of experiencing "wilderness" that apparently had vast appeal!

Picture of a dude ranch trail ride from the Adirondack Museum

Journal article on Dude ranches in the Adirondacks

Relevant portion on dude ranches from "Arizona and the West"

But while looking up these ranches, I happened upon an article talking about dude ranches in the Adirondacks. Apparently, after the era of the great camps, and starting around 1930, a large number of ranches sprang up in Warren County (Lake George/Sacandaga area) to the point where Warren County was known as the dude ranch capital of the East. They basically provided a Western flavored vacation experience including horseback riding and some rodeo action. People would come from the cities to meet the cowboys and to be in that sort of vacation atmosphere. The ranches even imported some cowboys from the West, and remained popular until the 70's and 80's when the focus of the tourists changed yet again. Some continue to exist today with slightly changed business models.

While this may seem corny to most (it would to me too if I had never heard of a dude ranch), I would argue that it's just another way of experiencing "wilderness" that apparently had vast appeal!

Picture of a dude ranch trail ride from the Adirondack Museum

Journal article on Dude ranches in the Adirondacks

Relevant portion on dude ranches from "Arizona and the West"

Winslow's Watercolors

As I was browsing through the powerpoint of Adirondack paintings, one of Winslow Homer's watercolors caught my eye. It was titled "An October Day," and was completed in 1889. Coincidentally, it was one of Ianna's slides today in her Winslow Homer presentation, so we got to further analyze it beyond what I had thought about the night before sifting through the powerpoint.

I had originally chosen that painting as my favorite in the powerpoint not because of what Ianna talked about in her presenation but purely on the aesthetics of the painting itself. I was really amazed about the way Homer was able to portray the glassy water. It's like the reflection of the trees was immaculately transcribed right onto the still surface of the lake. Also, the way the deer is majestically positioned in the lake, leaving a trail of disturbed water lapping behind him, brings a component of life into the otherwise isolated and pristine landscape.

Giving the image a second look, I noticed the little man in the boat in the lefthand corner. As we talked about in class, we don't know whether this man is just observing the deer, or whether he hunting the deer. Regardless, the inclusion of this man nonetheless brings a human presence into the wild. In some of these scenic landscape paintings, I think we sometimes tend to forget the impact that humans had on the park.

Being interested by this painting, I looked up some of Homer's other Adirondack watercolor paintings and each one was more beautiful than the previous one. Watercolor seems to lend itself very well to the subject of Adirondack painting.

Giving the image a second look, I noticed the little man in the boat in the lefthand corner. As we talked about in class, we don't know whether this man is just observing the deer, or whether he hunting the deer. Regardless, the inclusion of this man nonetheless brings a human presence into the wild. In some of these scenic landscape paintings, I think we sometimes tend to forget the impact that humans had on the park.

Being interested by this painting, I looked up some of Homer's other Adirondack watercolor paintings and each one was more beautiful than the previous one. Watercolor seems to lend itself very well to the subject of Adirondack painting.

All photos from: http://www.geocities.ws/coverbridge2k/artsci/winslow_homer_adirondack_watercolors_2.html

Adirondack Art

When visiting the Adirondack

Museum, I loved looking at their art gallery. I thought their extensive

collection was very impressive. I have always loved looking at art because just

as we said in class, you cannot interpret a painting incorrectly. Art makes you feel a

certain way due to our own frame of mind and I think that is wonderful.

In the Adirondack Museum, I took a picture of a

painting entitled “Lake George” by Richard William Hubbard that stuck out to me. Richard William Hubbard was a member of the Hudson River School,

known for their interest in painting majestic American landscapes. He was born

in Connecticut, attended Yale College, and after pursued his painting

career at New York University under Samuel Morse. He traveled to Europe

briefly, reflected in his painting aesthetic upon his return. He frequently

visited the Adirondacks and the Catskills, which he drew great inspiration

from.

Another artist that struck me was

Rockwell Kent. I did not see his painting specifically in the Adirondack

Museum, but we did learn about him during our trip to Asgaard Farm, where he

lived beginning in 1927. He was born in Tarrytown, New York and studied architecture

at Columbia University.

Although he also drew inspiration

from the Adirondacks, he has a different aesthetic than Richard William

Hubbard. Kent uses a lot of broad, flat, colorful shapes while Hubbard is much

more detailed and stylistic. However both conveyed to me a very similar

message. I felt at peace in both paintings. I could almost hear the utter quiet

very rarely experienced in our world today. Both these paintings brought me

back to a specific moment at Litchfield Castle. On the Sunday morning before we

left the Adirondacks, I ventured out to the back porch at Litchfield. I stopped

and listened and for one of the only times in my life I heard absolutely

nothing. There were no roads or houses near Litchfield, something that is hard

to achieve, and we were completely alone in the wild. In both these paintings

there are signs of human life, like the farm house in Kent’s painting or the

boat in Hubbard’s, but to me it felt like I was that human presence and there

was no other humans around, just like at Litchfield.

|

| Rockwell Kent Untitled: Asgaard Farm http://www.adkmuseum.org/discover_and_learn/collections_highlights/detail/?q=rockwell+kent&cat=0&type=0&x=0&y=0&id=28 |

|

| Richard William Hubbard Lake George, 1865 Adirondack Museum |

Early Adirondack Photography

Today in Onno's class, we talked about some of the early Adirondack painters, including Thomas Cole and Winslow Homer. We talked a bit about the reasons for artists to paint the Adirondacks in the first place, and about how art was a way to advertise the Adirondacks, or to describe the wilderness to people who could not Htravel there. I wondered if photography also played a role in advertising the Adirondacks, so I did a little bit of research and found a lot of information about a photographer named Seneca Ray Stoddard who published an illustrated guide book of the Adirondacks in 1873. He was brought to speak to the NY State legislature and used photographs to help persuade them to create the Adirondack Park.

Photo by Seneca Ray Stoddard

The peak of romantic art in the Adirondacks, the late 19th century, was also a time when the camera was being used more and more frequently. I think it is interesting that both paintings and photographs were used to promote tourism and conservation in the Adirondacks. Photographs provided a concrete, obviously realistic image of something that actually existed in the Park, while paintings were an artists impression of an aspect of Adirondack Wilderness that was less "realistic" but allowed for a lot of artistic freedom.

"Adirondack Evening", by Peter Corbin

Peter Corbin's painting has a similar subject matter to Stoddard's photograph. Although a viewer of the painting would not be sure that it is an accurate representation of the Adirondacks, its use of color in some ways makes the painting feel more realistic than the photograph. I wonder if the publications and advertisements of the time had a preference for photographs over paintings or vice versa, or if one type of image was considered "more valuable" or "more artistic" than the other.

Great Camp Santanoni

I chose to present on great camp Santanoni for class last week, I was amazed at the debate around preserving the 45 buildings, built in 1893, that are now owned by the state. Here are some of the main pros and cons surrounding this debate, let me know what you think!

Pros:

Pros:

- Great Camp Santanoni is built almost entirely out of native trees, the great lodge alone boasts 15,000 trees (most of which are used in either full log or half log construction). This makes the camp uniquely rustic and full of Adirondack character.

- The Great Camp is Historically significant; the owners and founders of Great Camp Santanoni once hosted Teddy Roosevelt. Also, the Santanoni farm was the largest great camp farm on record, it used to export milk, meet, and cheese to Albany and the surrounding areas in NY. You can still find citizens with Santanoni milk containers in the surrounding counties.

- Great Camp Santanoni is a tourist attraction. The camp borders the town of Newcomb, which desperately need the money from tourists interested in visiting the camp.

Cons:

- The cost of preserving all 45 buildings, mostly made of wood and other decomposable materials, is extremely high. AARCH has fundraised over 1 million dollars for past repairs and restorations of the property. However, there is more work to be done.

- Visiting is difficult, the Great Camp borders Newcomb, just south of the high peaks and visitors have to park their cars and walk, bike, horseback ride, or ski the rest of the 5 mile trail through the camp's main property (there and back).

- Continued upkeep is necessary. The camp is constantly exposed to the elements and the buildings are over 120 years old. There will always be rotting wood and caving roofs on property that is so old.

Great Camp Guilt

Reflecting on last class, I can't help feeling guilty about the exorbitant amount of resources that I planned to use in the design for my great camp. All semester we've studied how human beings have taken advantage of Adirondack land and altered the wilderness, and yet my ideal Adirondack camp is a multistory treehouse that would destroy much of the ecosystem around it. I am ashamed, both of the damage that my great camp would cause to Adirondack land and of my need for modern amenities. It is hugely ironic that I would recommend existing great camps be left to rot for their negative impact on nature and yet design a vision of "wilderness" that includes all the luxuries of a modern home.

Looking over my group's design drawing, I found that almost every aspect of our camp had potential negative impacts on the land around it. The foundation of our camp, consisting of houses supported by two separate trees, would greatly alter habitats for many Adirondack species and put a huge strain on the trees themselves. The house would likely produce a lot of waste that, if not properly disposed of, could poison the land around the trees and make it uninhabitable. The river passing by the two trees would be interrupted by the water wheel that we optimistically designed for renewable energy, possibly altering the migration patterns of spawning fish. The chair lift to the front door is an unnecessary waste of fuel and would require the clearing of a path through the trees in order to function. The chair lift also features windmills on top of each chair that would likely produce little energy being below the treeline and shielded from the wind, but might be hazardous for passing birds. Overall, I can imagine the camp being very comfortable for humans but an enormous strain on the environment.

I am also ashamed of the principle set by my camp that modern luxuries are needed to enjoy the wilderness. I like to believe that I share Bill McKibben's romantic view of nature as something that should be respected and kept separate from society, but my ideal great camp design challenges this belief. With all of its comforts and features, the treehouse would hugely impact the land and would inject suburban living into what was previously wild. If my great camp was built, the land around it could no longer be considered "wilderness", and I hope that any design similar to mine will never be given a permit to be built.

Music, and its Cultural Significance to the North Country

Music often carries great cultural significance, so it is no surprise that the Adirondacks have their own rich and educational music history. Just like the slaves who used music as an escape after a long day of working in the fields, Adirondack folk music was born from loggers, singing and dancing after a day of work in the woods. These folk songs provided entertainment for the loggers and were mediums for them to express their emotion. As explained in the Lynn Woods article, the Adirondack folk songs of yesteryears provide a window into the past that is still very valuable today.

The loggers' songs often told tragic tales of the many dangers they faced. Folk ballads were most popular, long rambling stories accompanied by music. They recounted universal themes such as love, while also delving into Adirondack-specific details like log-jams. The songs are often long and unpredictable, just like the lives of the people who wrote them. Loggers did not know if they would come back safely at the end of the day, and this was reflected in their music. The Adirondack-brand of folk music is still practiced today. I attached a link to a performance by Chris Shaw that epitomizes the lively storytelling typical of Adirondack folk music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fpaD2Eb0qLY

The loggers' songs often told tragic tales of the many dangers they faced. Folk ballads were most popular, long rambling stories accompanied by music. They recounted universal themes such as love, while also delving into Adirondack-specific details like log-jams. The songs are often long and unpredictable, just like the lives of the people who wrote them. Loggers did not know if they would come back safely at the end of the day, and this was reflected in their music. The Adirondack-brand of folk music is still practiced today. I attached a link to a performance by Chris Shaw that epitomizes the lively storytelling typical of Adirondack folk music.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fpaD2Eb0qLY

Sunday, October 26, 2014

Red Rose Around the Briar

The Adirondack Life article makes frequent use of the fact that one of the most important forms of music in the Adirondacks is the ballad. Essentially, the ballad is one of the most narrative types of music. Generally it involves a rather simplistic plot line as some sort of character discovers something, in a very emotional form instead of a summary. It's normally a very evocative and sentimental song, which fits in well with the tradition of spoken narrative in the Adirondacks.

The song "Barbara Allen" that was mentioned got me interested. It's a rather slow song, chronicling a dying man as he pines over a fair lady named Barbara Allen. Upon hearing that the man was so into her, Barbara is so overwhelmed with grief that she resolves to die for him the next day. (The mother dies the next day out of love for both of them) A little melodramatic, yes, but very indicative of a romantic sentiment that continues in folk tradition to this day. A lot of these songs were passed alongside immigrants (the song in question originated in England, the lyrics website suggests the song has a large Southern presence as well) in logging camps, specifically when the men lived in the logging camps together. In this light, the proliferation of a story about a dying man who has a woman waiting for him in death gives a very tragic and longing perspective on their day to day lives in the camp.

http://freepages.music.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~edgmon/stbarbarallen.htm

(Lyrics are here)

The song "Barbara Allen" that was mentioned got me interested. It's a rather slow song, chronicling a dying man as he pines over a fair lady named Barbara Allen. Upon hearing that the man was so into her, Barbara is so overwhelmed with grief that she resolves to die for him the next day. (The mother dies the next day out of love for both of them) A little melodramatic, yes, but very indicative of a romantic sentiment that continues in folk tradition to this day. A lot of these songs were passed alongside immigrants (the song in question originated in England, the lyrics website suggests the song has a large Southern presence as well) in logging camps, specifically when the men lived in the logging camps together. In this light, the proliferation of a story about a dying man who has a woman waiting for him in death gives a very tragic and longing perspective on their day to day lives in the camp.

http://freepages.music.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~edgmon/stbarbarallen.htm

(Lyrics are here)

We See What Matters

Looking back to the Adirondack museum and the items on

display, Adirondack art consists primarily of landscape images. The dramatic

High Peaks, most often Marcy, rising above the valley floor, and the many

rivers which bisect the park feature most frequently in Adirondack-inspired

paintings while the many crafts and goods produced within the park are earthy:

made of wood and bark of different shades, as if found in nature itself. The

art had relatively little historical context, lacking the strong religious

images that dominate European art, or the abstract, modern art seen elsewhere;

the land was pictured as it was (and is). In this sense, Adirondack art

represents what is truly paramount within the Blue Line: the landscape. It is

the landscape that dictates where humans settle and how they fare; and how and

where plants and animals could grow. There are few places in the northeast

where such a distinction is still so apparent, and so humans have tried to

replicate it. Crafts of the region share a similar functionality-driven

inspiration. Chairs and canoes are the defining Adirondack craft, all built

from wood and initially possessing an intrinsic utility. Such crafts further

adhere to the paradox of the park in that they, despite their utility, are

luxuries of the wealthy. Guide boats and lounge chairs were hardly necessary for

survival, but they were used extensively and played a large role in the initial

tourism economy of the park. Adirondack

art represents exactly what was important to those who created it, and mimics

the dynamic seen in other elements of Adirondack life.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)